The government of Japan is clearly intending that the 2020 Olympics will function as a public relations win in which the image of Japan, and especially of Northern Japan and Fukushima are cleansed of images of radiological contamination. Even as the Fukushima Daiichi site itself, and the traces where the plumes of its explosions deposited fallout throughout the area remain un-remediated, the public perceptions will be remediated. This is typical of the behavior of governments in the developed world that suffer radiological disasters. The disasters themselves are so difficult to clean up, and take decades to even begin the clean up, that money is allocated for extensive public relations efforts. These become tasks that CAN be completed and CAN be considered successful. They function both to advance the public image agenda of the governments, and also deliver a sense of agency when the overall tone of nuclear disaster remediation is one of lacking effective agency.

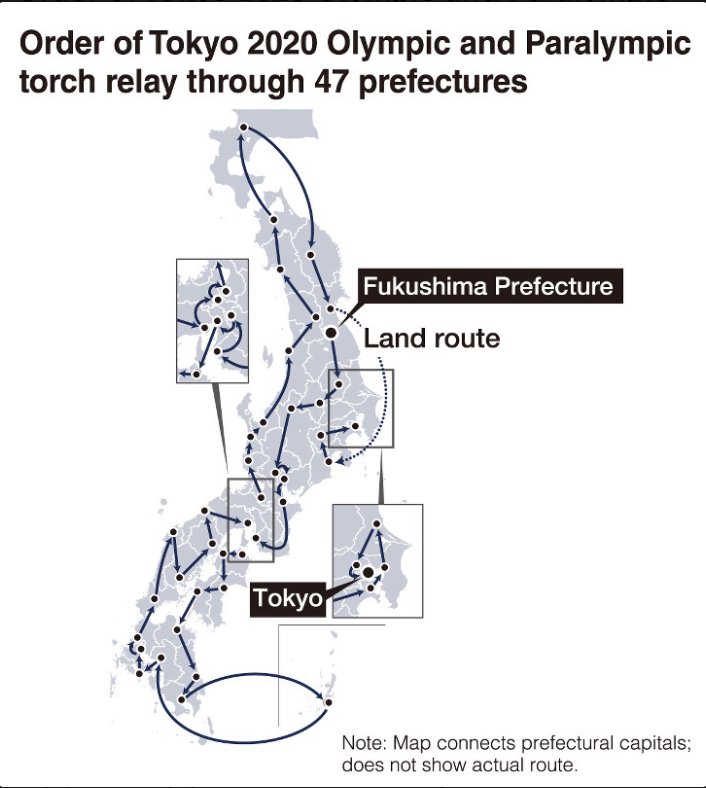

Towards that end, the Japanese government is planning to integrate Fukushima sites and perceptions into the upcoming Olympics media fest. The journey of the Olympic torch through every prefecture of Japan will begin in Fukushima, a symbolic rebirth intended to facilitate the repopulating of the local communities that were evacuated, many of which have had few returnees since the government has declared them "safe" and cut public funds to those forcibly evacuated.

The government is also planning to hold multiple Olympic events in Fukushima prefecture including baseball and softball events. "Tokyo 2020 is a showcase for the recovery and reconstruction of Japan from the disaster of March 2011, so in many ways we would like to give encouragement to the people, especially in the affected area,"said Tokyo 2020 president Yoshiro Mori last March.

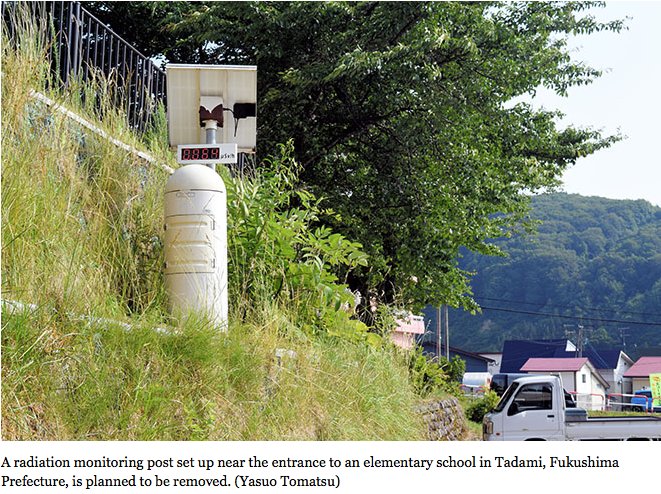

This active rebranding of Fukushima as safe involves removing physical reminders of ongoing risk. The central government has recently announced that it will be removing 80% of public radiation monitors from the region. An argument can be made that the presence of these monitors is theatrical in that they only measure external gamma radiation levels, which are not the primary risk to residents (this comes from internalizing radioactive particles that blanketed the region in the fallout of the plumes of the explosions of March 2011), and that positioning these gamma detectors in midair produces low readings since the particles are primarily on the ground. However, they are a tangible, embodied reminder that risk remains.

(From Asahi article in the link above)

Another step to remediate the image of Fukushima is the opening of a highway previously closed because it passes through an area of high contamination that is not open to habitation. "A Japanese NGO posted these photos to social media showing signs installed on the newly opened highway 114 near Fukushima Daiichi. The signs tell people to “pass through as quickly as possible” and are in English. This stretch of highway borders the zone of highest radiation from the disaster and runs just north of Fukushima Daiichi towards Fukushima City," describes an article posted on the SimplyInfo site (note: I am a member of the SimplyInfo research collective). Here is the photo referred to above:

While there is a clearly an active campaign to rehabilitate the image of the region leading up to the 2020 Olympics, an effort that will no doubt intensify as the event draws near, there is also pushback and resistance in the local and national communities. A recent sculpture unveiled at the JR train station in prefectural capital Fukushima City (about 80km from the Daiichi nuclear site) has been stirring up controversy. A Guardian article explained:

"The statue, by Kenji Yanobe, depicts a child dressed in a yellow Hazmat-style suit, with a helmet in one hand and an artistic representation of the sun in the other.

Yanobe said his Sun Child, which was installed by the municipal government after appearing at art exhibitions in Japan and overseas, was intended to express his desire for a nuclear-free world.

The artist said he did not mean to give the impression that local children needed to protect themselves from radiation more than seven years after the Fukushima Daiichi plant became the scene of the world’s worst nuclear disaster since Chernobyl.

He pointed out that the child was not wearing the helmet and that a monitor on its chest showed radiation levels at '000'."

Yanobe's "Sun Child" statue in Fukushima City

While some, including the mayor of Fukushima City, have praised the statue for emphasizing a hopeful future for local children, others have criticized the statue for suggesting that there is any danger to local children.

Regardless of how one interprets the sculpture, it does confront people with the fact that things are far from normal in the region. This, in spite of the central government's strong efforts to implore people not to pay any attention to what is happening behind the curtains it has been raising.