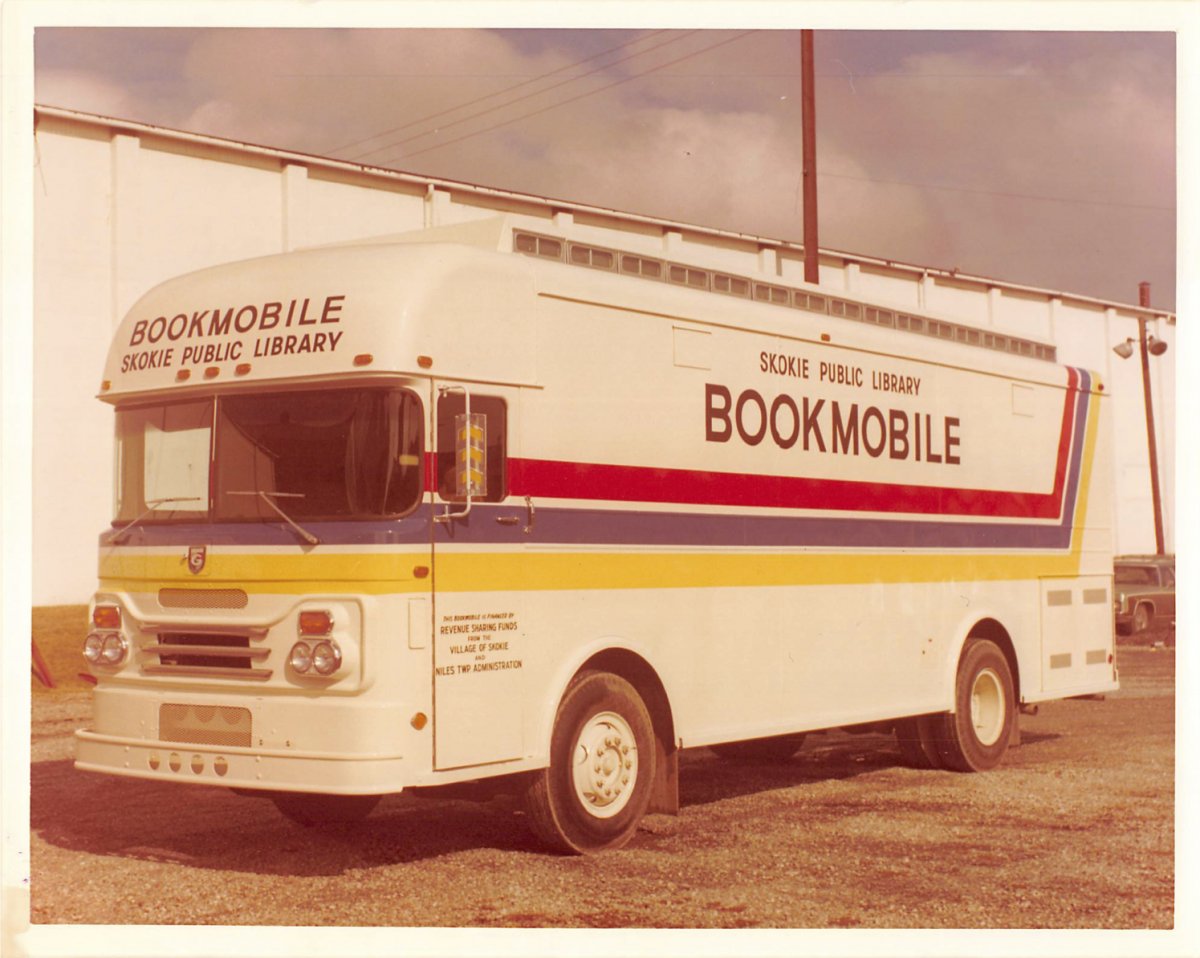

I grew up in a non-descript, older suburb on the Northern border of Chicago named Skokie. No one who isn’t from the area should even know the name of Skokie, but probably many of you do. Skokie was 58% Jewish when I was growing up there in the 60s and 70s, the largest percentage of any Chicago suburb, and included in that number was over 8,000 Holocaust survivors. Many of my friend’s parents and extended family (that had survived) were Holocaust survivors. My neighborhood was almost entirely Jewish (as is my family) and there was even a small subdivision nearby that was known as “where the Christians lived.”

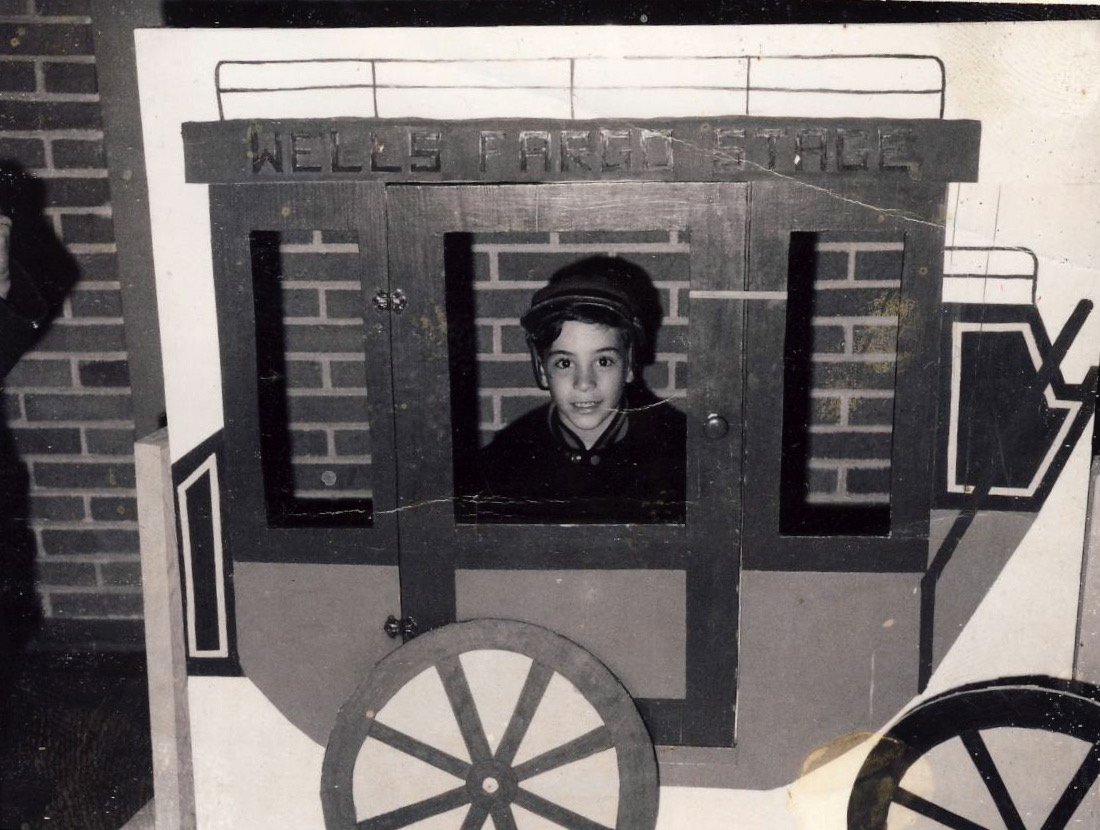

At a fair at my school in April 1967

The Skokie of the late 1960s and early 1970s felt like the safest place on Earth. We kids were utterly carefree and left our bicycles in front of the drug store or grocery store unlocked without any sense that they might not just be sitting exactly in the same spot when we returned. Against that implicitly felt safety though, were the admonitions of the generation before us, especially the Holocaust survivors. My family did not have Holocaust survivors, our ancestors came to America escaping the shtetls of Eastern Europe at the turn of the century. But often at friend’s houses, their parents or grandparents would say to us—don’t be so sure that it will always be safe here, things could change in a second and we could lose everything. They sounded a bit like Grandpa Simpson would later sound. Sure, sure we thought, they just say that, but nothing can happen here. That happened there, in the old country. And we went outside and played Capture the Flag or Statue Maker.

This was the late 1960s, and for those who had endured and survived the Holocaust, this was only a little more than 20 years before, and clearly it was still visceral to them. They felt almost as though it had “just happened.” But to us, it was worlds away. We did study the Holocaust in temple every year, and also the long history of anti-Semitic attacks against the Jews in Europe. We are a historical people by nature and we were schooled in Jewish history, which includes a litany of traumas and tragedies, from Biblical times to the pogroms of our millennial passage through Europe.

These Holocaust survivors were trying to convey to us what they knew to be true: that a society that was nominally inclusive of “outsiders,” that provided public safety for a majority of its population, and that had democratic and social institutions standing as barriers to political violence, could be pulled apart more quickly than you could believe. They told us that all of the safety and comfort we knew in our post-war suburban community was fragile. They told us to be vigilant. We imagined that we were humoring them when we listened, but we laughed about it when we were out on our bicycles later.

As I grew up I came to understand that many of my assumptions of that time were naive. I realized that the safety and inclusion that I felt in my town were not extended to large communities in my country, that black people did not live with the same lack of violence, that Native American communities did not live with the same sense of safety. I came to understand how tribal and colloquial my own community was. All of our temples had signs that said “Never Again” in response to the Holocaust. As a child I thought that meant that my community would always stand against genocide because of what had happened to us. It was a rude awakening in my late teens when, as the Cambodian genocide was unfolding I realized that none of the temples or community leaders in Skokie were saying anything about this genocide. It dawned on me: never again meant never again to us. That was a real political awakening for me. What I had thought was an ethic, was more like a tribal cry of self-defense. I came to realize that the state of Israel, which we had all championed as youths, was engaging in horrible treatment of the Palestinian population of the country. When we were told that Israel had risen out of the ashes of the Holocaust to help breath life back into the Jewish community, it has exercised power like other repressive states, not like a flower that rose from a mass grave. These things helped me to mature as a political person and grow out of the simple black and white world in which I had been raised.

When the National Socialist Party of America tried to stage a march in Skokie in 1977 and 1978, and fought a court case over their right to march there, I understood that it was meant to provoke fear and terror. I could tell that if they did march in Skokie, there would be violence. This was the part of Never Again that I realized was functioning fully. Those Nazis seemed pathetic, very close to the "Illinois Nazis" that would be so effectively satirized in the 1980 film The Blues Brothers. It was clear that the Holocaust survivors in Skokie were prepared (as was most of the rest of the community) to stand up to Nazis coming into their community again. The threat did not seem real, but for many in Skokie there was a sense that the threat was very real, however pathetic the messengers were that time.

But now, today, I feel that I am living in the world that the Holocaust survivors of my childhood had been warning us about. Anti-Semitism is rampant in American society. It is being shouted from the highest political rooftops and the wealthiest cable news network. This anti-Semitism is not alone, any more than it was in Nazi Germany. Countless groups of “others” are being demonized and violently attacked. The “safe” democracy that I grew up in feels to be on the verge of a cliff over which it may tumble easily. Those survivors don’t seem like Grandpa Simpson to me anymore, but more like a time-travelling me from the future that had come back to warn teenage me about what was coming.

We cannot take for granted that the world around us is stable. It is only as stable as we make it. It is not a landscape; it is not close to permanent. It is a work in progress. We can’t stop making it inclusive for those who suffer. We can’t stop standing up to violence and hate. We make this world every day and we have to show up every day to keep it healthy and able to bridge us to one more tomorrow, and then we have to wake up and do it all over again. This I know to be true because it was told to me by my elders when I was a child in Skokie.