Several years ago, I was speaking with a prominent Anthropocene scholar in Uppsala, Sweden. We were in disagreement about the risks to the environment of nuclear power. For both of us, Chernobyl was part of making our case to each other. He told me that if the radiation around Chernobyl was so dangerous, it would not now be as full of returning wildlife as it has become. Animals are becoming more abundant there, he explained, so it shows that things are not as dangerous in the Exclusion Zone as people assumed it would be. This framework is actually quite common in press reports about Chernobyl, especially since the Zone has become a tourist draw during the last few years.

"Wildlife is thriving in Chernobyl as scientists snap adorable image of an otter living in the Exclusion Zone," warmly declares a reassuring headline from the Daily Mail. This story, like many others, were part of the media reaction to the publication of a study that found significant levels of wildlife, especially mammals, were populating the Exclusion Zone since humans had been forcibly evacuated in 1986. The study had placed hidden cameras in the field in sites around the Zone and produced images of a wide variety of species over a period of several weeks. In another study, researchers had also placed fish carcasses in locations and tracked how quickly and fully the fish had been scavenged by wildlife in the Zone. While the researchers were generally cautious about their findings, explaining that the abundance of animal life was an expected effect of human abandonment of a region rather than that radiation was not dangerous, their study was widely embraced by media sites, who declared, for example, that, "Chernobyl is becoming an unlikely poster child for...environmental renewal." The Daily Mail story drew it's own conclusion that, "Radiation levels are still too high for humans to return but wildlife have moved back to the zone and are now thriving," and, "This most recent study shows that semi-water based wildlife, like otters and minks, can live in the zone."

The "adorable" otter in the Chernobyl Exclusion Zone (UGA)

While the stories of wildlife abundance in the Chernobyl Exclusion Zone can be heartening, the notion that this by itself tells us anything about the risks of living with radiation are silly. One of the most terrifying things about being immersed in a radioactive environment is that the presence of radiation is imperceptible. We cannot smell, taste, see or feel radiation. We may be receiving enough radiation to kill us and we would not sense danger. Narratives like the above about the presence of animals in the Exclusion Zone showing that life can thrive there are incoherent. Are we to believe that these animals are capable of sensing radiation while we humans cannot? That they are there because they can tell that it is not dangerous to their long-term health?

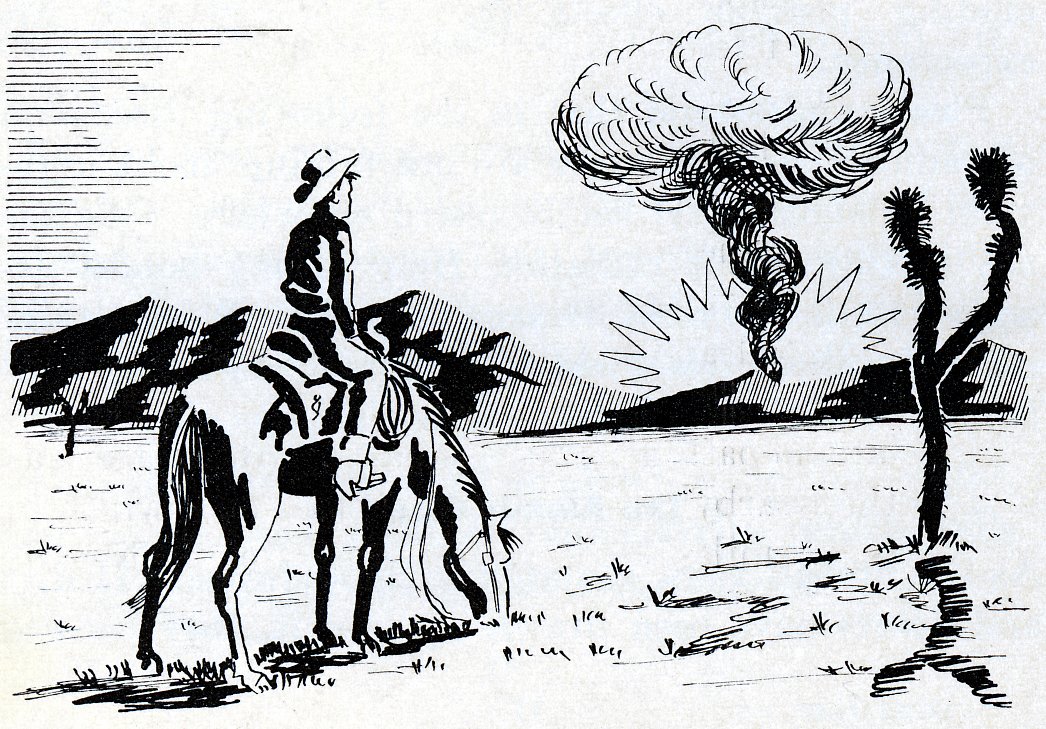

These tropes of the "natural wisdom of animals" are self-serving and deceptive. They have been used to calm humans about radiation for decades. Here is an image from a pamphlet distributed to people living downwind of the Nevada Test Site by the United States Atomic Energy Commission in 1955.

From Atomic Tests in Nevada, 1955 (AEC)

The purpose of the pamphlet was to calm their fears about radiation from the repeated testing of nuclear weapons upwind from their homes and ranches. The key to this image is the horse. While the cowboy (the downwinder) looks at the mushroom cloud over the horizon with concern, the horse--who instinctively demonstrates the natural response to danger--is unconcerned. The cowboy should learn from the horse: these tests are benign. The same use of the natural wisdom of animals can be seen in the graphic below from the magazine Picture Parade from 1953. The dog knows that the boy (in the clothing that resembles an American flag) has nothing to worry about from the radiation drifting towards him in the fallout cloud. All is well. The animals know this.

From Picture Parade, 1953

Numerous studies (for example here) have found that there are dangers, and genetic abnormalities in many species of birds and animals that live in the Chernobyl Exclusion Zone. The presence of animals in a radioactive ecosystem is no proof that these same animals are not in danger. Rather, they are proof that once humans withdraw habitation, many other species will fill that gap. This is true in Fukushima, Chernobyl and many other radiologically contaminated places. Jim Smith, one of the authors of the study photographing the wildlife in the Exclusion Zone told reporters as the study was being popularized that this "does not mean that radiation is good for wildlife." However, Smith then added, "It's just that the effects of human habitation, including hunting, farming, and forestry, are a lot worse," That may be another overstatement.

Many of the radionuclides that are deposited in the Exclusion Zone include particles of plutonium and uranium, which will still be harmful to animals over the course of hundreds of thousands (PU) or millions (U) of years. Humans may be long gone from the Zone, or the planet, and yet there will remain significant dangers to animals that inhabit the area. These dangers, from the Chernobyl disaster, will last longer than human hunting, farming, and forestry have existed in our previous history.

Educational model of the DNA structure in an abandoned school in Pirpyat, 2019 (taken by author)